Between modern day logging and fires, the types of trees and plants that once covered ancient Book of Mormon lands is near impossible to ascertain. With the discovery of ancient forests in key areas of western New York it is now possible to ascertain what those trees and plants were and possibly to discover the ancient herbal remedy spoken of in Alma 46:40.

The protected locations are: The Lamanite Line of Possession (Cattaraugus Gorge), in the Sea that Divides the Land (Lake Tonawanda), and along the Sea West (Niagara Gorge). The following newspaper articles discuss the discoveries.

Western New York Forestry

Amazed by tall trees

Expert’s spirits soar

discovering the giants of Zoar

by John F. Bonfatti, News Staff Reporter

Buffalo News, Sept. 24, 2001

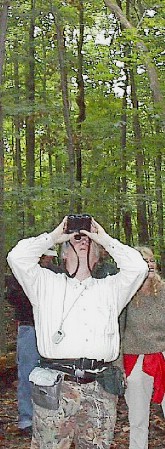

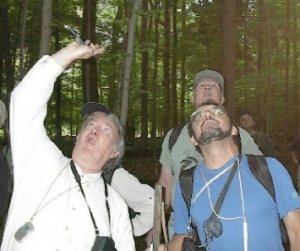

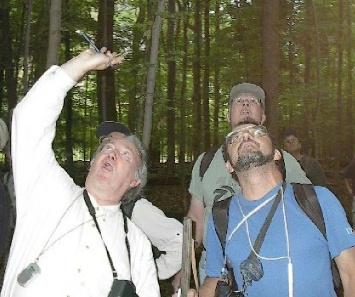

PERSIA, New York—Bob Leverett craned his neck as he searched for the treetops in the “gallery of giants” along Zoar Valley, straddling Cattaraugus Creek. “The soar of Zoar,” he said in amazement.

Leverett, considered by many to be the nation’s foremost expert on old-growth forests, was in Western New York during the weekend to determine whether old-growth sites here contain some of the tallest trees in the Northeast. He was not disappointed.

|

|---|

“I never dreamed these trees would soar like this,” said Leverett, who has measured more than 10,000 trees in the eastern half of the country using a laser range finder, an inclinometer and a calculator. “The canopy of this forest is way above 100 feet.”

Try 50 feet above, in some cases. The tallest tree Leverett measured in trips to Reinstein Woods in Cheektowaga, the forest at Lily Dale and Zoar Valley was a 151-foot specimen here that he said was the second-tallest sycamore in the East, and the tallest north of the Smoky Mountains.

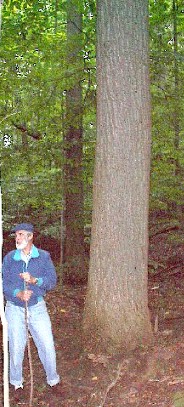

The trees here, among them black walnuts, red oaks and poplars, are among the oldest living things in the area. They have avoided the logger’s chain saw because of their remote location in an area that many in Western New York have heard about, but few have seen.

Leverett and about two dozen interested parties trekked several miles down into the valley Saturday on a primitive trail and then forded the creek three times to view the behemoths.

“Holy Toledo!” Leverett kept saying as his eye caught a particularly impressive tree. “This place is awesome. It is beyond my expectation.”

Indeed, Leverett said he would be “kicking myself all the way back home” for not taking up Bruce Kershner’s offer to tour the forests in Western New York sooner.

Kershner, chairman of the Niagara Frontier Botanical Society’s Western New York Old Growth Forest Survey, said he had been pestering Leverett, based in Chicopee, Mass., to come here for years.

|

|---|

Kershner wanted help in verifying that the area is home to some of the state’s oldest, biggest trees. He fears that the state Department of Environmental Conservation, which is making a master plan, may allow logging.

“He is an authority that is not questionable,” said Kershner, who also is conservation director of the Buffalo Audubon Society. “We want to be able to document that we have champion trees as well as old-growth forest. They are irreplaceable.”

Some are also very valuable. Kershner estimated that one black walnut tree, which Leverett measured at 116 feet tall, would be worth $8,000. One of the hikers, Becky Nystrom of Jamestown, countered, “It is a priceless tree.”

Around the corner from Skinny Dip Falls, Leverett found a tulip tree, also known as a yellow poplar, that was 140.2 feet tall. He said it was the tallest such tree he had measured north of New York City.

Other giants included a 130.8-foot red oak that was the tallest he had measured in the Northeast and a 133.1-foot cottonwood that was the tallest he had measured north of the Smoky Mountains.

At Lily Dale, Leverett measured a black cherry tree that was 131.2 feet tall, the second-tallest in the Northeast, in a group that he said was “one of the best stands I’ve seen for this longitude.” He also found a 115-foot-tall cucumber magnolia, the tallest measured in upstate New York.

And at Reinstein on Friday, Leverett found what he termed the largest beech tree in a New York forest. It was 103 feet tall and had a 43-inch diameter.

It might have taken Leverett a while to get to Western New York, but it’s unlikely to be his last visit: “I have got to come back.”

Ecologists find old-growth forest at Hemlock Lake

415-acre tract in lakeside ravines

has 500-year-old trees

by Corydon Ireland, Staff Writer

Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, Monday, September 25, 2001

GOWANDA, New York—About 415 acres of woods on the southwest shore of Hemlock Lake are untouched, ancient old-growth forest and may constitute the largest such tract in western New York. That’s the claim made by a group of forest ecologists in Buffalo, who have been researching, mapping and cataloging old growth forest remnants for more than a decade.

So far, they have mapped 24,000 acres of old growth in western New York on 57 separate tracts. The Hemlock tract—No. 57—is the largest find.

| Characteristics of ancient old growth forests |

|---|

“It knocked my socks off,” said Bruce Kershner of Buffalo, a nature writer and forest ecologist. “Parts of it looked like ancient virgin forest—the rarest of the rare—never touched by human beings, a chain saw or an ax.” His team visited the area in July and mapped it. They planned to return yesterday for further exploration and measurements.

On Hemlock Lake, the old growth is tucked into some forbidding terrain, marked by at least 15 steep ravines that slope towards the lake. It’s owned by the city of Rochester, part of 7,200 acres of city-owned land bordering Hemlock and Canadice lakes, which supply the city’s water system. Edward Doherty, Rochester’s commissioner of environmental services, said the city’s forest management plan has inventoried the land around the lakes, but does not make clear that any of it contains old-growth forest.

“We’d like to see what their information is,” he said of the Buffalo-area researchers. If the claim is true, added Doherty, the city would probably forgo any plans to log or add logging roads in the area.

Don Root, the city’s watershed conservationist, said he was aware of very old trees along steep portions of the Hemlock Lake shore—but would like to know more about how the researchers define “old growth” forest. Within three weeks, he said, the city will meet again with the Sierra Club, Rochester Region, area landowners and others concerned about the issue.

“We’re looking at (the old growth claim) more closely now,” said Root.

|

|---|

The realization that the Hemlock tract was so large—about 2.5 miles long—took the Buffalo scientists by surprise. One fallen hemlock tree there had 515 rings, one for each year, making it a seedling before Columbus made his famous voyage.

“It was like counting the grooves on a vinyl record,’ said Kershner.

He said the tract exceeds in size and botanical complexity a 400-acre area of old growth forest in Allegany State Park, two hours south of Rochester. An old growth tract is assessed by dating tree core samples and by noting features of old growth forests. Those include undulating forest floor terrain, a lack of uniformity in tree height and unusual biological diversity.

Kershner and his team have recorded old growth tracts in counties as far east as Wayne County, as far south as Allegany and as far west as Erie and Niagara counties. Near Rochester, there are old growth remnants in Bentley Woods, near Victor, Ontario County; in the privately owned Big Woods area of Webster, bordering Lake Ontario; and at Hemlock Knoll, a five-acre patch within 1,800-acre Bergen-Byron Swamp in Genesee County.

Unlike wetlands, old growth tracts are not formally mapped or protected by the state. But academic authorities estimate that New York has about 350,000 acres of old growth forest, mostly on public land in the Adirondacks and the Catskills.

Author and old growth expert Robert Leverett of Holyoke, Massachusetts, one of the founders of the Eastern Native Tree Society, was expected to visit the tract yesterday. “It certainly exceeds our expectations, given what we had assumed survived” in western New York, he said. “The assumption was that the rest of New York would have a spot or two here and there of 5 or 10 acres.”

|

|---|

Kershner and others estimate that western New York has retained about 0.25 percent of its original forest cover. Whatever survived was preserved in estates of the wealthy; in areas set aside by fiat, including the Adirondacks; and in steep, remote areas that were hard to reach with the logging technology of the 19th century.

Leverett said old growth tracts give scientists a rare glimpse of a primeval forest’s intense complexity, including canopy-limb lichens that help fix nitrogen and colonies of underground fungi that stretch for acres. They might also provide a sort of biological baseline for research into global warming. And such places have cathedral-like aesthetic value, as living remnants of pre-settlement history, said Leverett.

“They shake us back into reality about the grander order of things.”

Leverett and Kershner have co-authored a book, The Sierra Club Guide to Ancient Forests of the Northeast, which will be published at this time next year by Random House. It will include about 20 examples in the western New York and Finger Lakes regions—though not the Hemlock Lake tract, which is too hard to get to.

Leverett planned to measure the height of trees in the old growth tract, using a laser range finder and other high-tech tools.

The Hemlock Lake old growth includes stands of hemlock, evergreens and maple on steep slopes. Most surprising, said Kershner, are its stands of hardwoods like oak and ash growing on relatively flat terrain. Normally, such trees would have been the first to fall to the logger’s ax, he said.

Team uncovering woods that date back centuries

by Corydon Ireland, Staff Writer

Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, Sunday, February 18, 1996

PITTSFORD, New York—It’s a short ride to the old woodlot behind John Hopkins’ on Clover Road. The pickup truck sways and creaks along a rutted road bordered by a wide field, stubbled with cornstalks.

Three minutes, tops.

Or 200 years.

“Time travel” is one way of describing a visit to this isolated 25 acre patch of red maple, birch and tulip trees, some over 200 years old. Hopkins, a descendant of the man who founded Pittsford, grew up playing in the miniature forest that experts say is one of the last remnants of old-growth trees in western New York.

A team of five amateur and professional botanists from the Buffalo area, working over six years in their spare time, has uncovered 29 places dominated by trees at least as old as the United States. This find is one of a series of discoveries, often by enthusiastic amateurs, that in the past decade has revealed more than 3 million acres old old-growth remnants. That’s up to five times more than experts had estimated.

| In western New York, trees estimated to be 400 to 500 years old have been found in Letchworth State Park, while 1,300-year-old trees have been discovered in Zoar Valley in Erie County. To qualify as old-growth, a tree must be at least 150 years old. |

Old-growth tracts provide intricate habitats for wildlife, are living laboratories for forest ecologists, and provide most of us with a nourishing sense of history and natural beauty. But these natural treasures—which have survived centuries of human encroachment and natural disaster—have little protection under the law. The new survey of western New York’s old-growth may heighten public awareness, spurring future protections.

Bruce Kershner Chair, Friends of Alleghany  |

|

PHOTO: David Yarrow 2001 |

Bruce Kershner, a Buffalo-area forest ecologist who helped compile the study, calls it “historic.” As chair of Friends of Alleghany, Kershner led the group that helped bar commercial logging at 67,000-acre Alleghany State Park in Cattaraugus County. “This is not about discovering a place with some big, old trees,” he said. “This is the original landscape before the white men came.”

View downstream from the “Gallery of Giants” in Zoar Valley  |

|

PHOTO: David Yarrow 2001 |

Survivors

The western New York sites are scattered over 11 counties covering 8,397 square miles. They total 1,275 acres so far, with 44 likely sites still to be examined.

“We should have brought a horse and sleigh up here,” says Hopkins, stepping out of the pickup truck into a fresh cover of snow. His family woodlot is within honking distance of Clover Road, which last week sizzled mid-afternoon traffic. A musket shot away, dozens of houses have sprung up in old cornfields.

The sloping patch of woods, by West Coast standards of old-growth forest, is not dramatic. East of the Mississippi, old-growth forests—in patches that add up to an estimated 4 million acres—can be scrubby and humble. Most of the trees have survived because they are in areas too wet, too rocky, or too vertical to be exploited commercially.

A 350-year-old sugar maple in Zoar Valley’s “Gallery of Giants”  |

|

PHOTO: David Yarrow 2001 |

“Our old-growth doesn’t look like the sequoias—it’s not spectacular,” said Jim Battaglia, an amateur botanist and one of the researchers. “But it’s spectacular in its own way, once you are sensitized to it.”

The Hopkins lot—the second largest western New York old-growth tract in private hands—is an exception. It wasn’t saved by inaccessibility. It was saved by foresight and family tradition dating back 185 years, when Col. Caleb Hopkins, a hero of the War of 1812, moved his family there from Pittsford, Vermont. Since then, the Hopkins touch has been light. Starting in the last century, the woodlot’s maples were tapped for sugar. And up until the 1920’s, trees were cut for cooking and heating. It’s still strewn with untouched glacial boulders and topped with maple, oak and tulip trees.

Will it stay wild and natural?

“I would personally like that,” said Hopkins, whose nephew and farming partner Mark Greene stands to inherit the property. “But I don’t know that it can be kept that way forever.”

Spare that tree

Seven privately held old-growth survive because of owners like Hopkins. Of the other sites, 16 are owned by the state or colleges, and six are overseen by conservation groups. But for old-growth forests in general, state and federal laws offer no legal protection.

“Wetlands are protected, no matter how ugly they are,” said Syracuse botanist Donald Leopold, noting that federal scrutiny starts at one acre. “But an upland forest, even if it is the most important in the country, has no protection.”

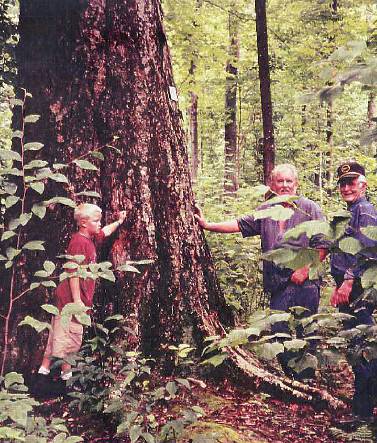

Bob Leverett and Bruce Kershner share excitement over a big tree in Zoar Valley  |

|

PHOTO: David Yarrow 2001 |

There are horror stories, said Robert Leverett, a Massachusetts amateur botanist who co-authored a chapter in a new book, Eastern Old-growth Forests: Prospectives for Rediscovery and Recovery (Inland Press, 1996), due out in March. In Maryland’s Belt Woods, he said, a stand of ancient oaks up to 400 years old was cut down for high-priced veneer by its new owner, a Presbyterian church.

State and federal forests offer a line of defense for old-growth. But even professional forest managers are bitten by “just plain poor ignorance,” Leverett said. “They carry a stereotype that nature is just a mess box and we have to come along and prune and make things a garden.”

Fifteen of the sites Kershner and his friends surveyed in western New York are 20 acres or more, making them forests, technically; 11 others—from one to 19 acres—are “groves.” The research group still has at least 44 sites to visit and asses, including a patch of woods along Irondequoit Bay. Other sites in Irondequoit, Webster Town Park and Rochester’s Pinnacl Hill. Were assessed and turned down as second growth tracts.

Their preliminary report, sponsored by Nature Conservancy and the Adirondack Mountain Cub, is unpublished.

| National Champion Yellow Birch Gould City, Upper Peninsula, Michigan  |

|---|

“We’re amateurs looking at areas no one else would think to look,” said Battaglia, a Buffalo-area high school English teacher with a passion for botany. “If you’re a graduate student, you’re going to go to the Adirondacks or Maine—not Rochester of Buffalo.”

Hidden treasure

Battaglia and the other researchers—three of them with formal scientific credentials—estimate that western New York’s forest cover of three centuries ago has dwindled to .025 percent of its original self.

Most old-growth remnants have survived by virtue of being undesirable, said Doug Larson, a botanist at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada.

“We’re starting off by asking the question: What kind of place would people leave alone?” he said. The answer is “cliffs, swamps and granite formations,” said Larson. “Accessibility is inversely proportional to old-growth places. The land most likely to be preserved is the hardest to get to.”

In 1989, Larson announced that he had found an ancient forest ecosystem clinging to cliffs along the 496 mile Niagara Escarpment in Canada. Some eastern white cedars found are 1,600 years old. Hardy and small, many of the trees grow less than a gram a year, eking nutrients out of seeps, fungi and rock-bound algae. Larson’s team members routinely dangle off cliffs to measure trees and bore out straw-size core samples so they can count rings.

Random acts of nature

Why care about remnants of old-growth forest?

Biological diversity, for one, said Leverett. Old forests have many types of habitat—”a mosaic of patches” created by nature’s “random disturbances,” he said. Large standing trees coated with moss, twisted root “snags” and rotting logs on the ground provide the means for a broad range of plants and animals to colonize. There’s some proof that some migratory birds are 45 times more numerous in old-growth forests than in younger adjacent forests, said Leverett.

| Common long-lived regional species |

|

|---|---|

| species | maximum height |

| Beech | 130 feet |

| Hemlock | 100 feet |

| White Cedar | 70 feet |

| Sugar Maple | 130 feet |

| Tulip Tree | 200 feet |

| White Ash | 130 feet |

| White Oak | 150 feet |

| White Pine | 200 feet |

Charles Cogbill, a Vermont-based forest ecologist and consultant, said the value old old-growth tracts “is still an open question.” It’s unlikely that many species depends on them. And even commercial interests might not be attracted to “beaten down woods” often dominated by stunted, gnarly trees.

“On the flip side,” said Cogbill, “I’ve been in a lot of (old-growth) places that are the key to my understanding of how forests operate.” Cogbill admits he feels torn between science and awe when in the presence of a stand of ancient trees.

Leverett acknowledges that “showcase stands” of old-growth—a few acres here and there-have less importance biologically and are more vulnerable. But they still have “historic value.”

And aesthetic value. “There’s a physical impressiveness” even to remnants of old-growth forest, said Leverett. “There’s a timeless feeling you get. It may be a sign of the way we evolved as a species.”

Arborist Fred Breglia in the Zoar Valley gorge. Behind Fred is the “Gallery of Giants.”  |

|

PHOTO: David Yarrow 2001 |

For whatever reason, interest among academics and amateurs in remnants of old-growth in the Northeast is picking up steam. “The fact is, they’re real,” said Leopold of the hidden tracts of old-growth that are starting to emerge even in the farmed-over East. Despite heavy development, he said, “a few got away.”

Quiet exoticism

One that got away is Hemlock Knoll in Genesee County, a five-acre patch of old-growth isolated for centuries by swampy ground.

To get there, you hike past a modern farmhouse along a wide gravel tractor trail—past flat fields where furrows edge out of hard snow like knife blades. At the brim of the woods, you see tree-dotted swampy flats sucked dry by winter. The path narrows to a corduroy trail of logs, edged with shoulder high cattail reed, erect and golden. Deer tracks pepper the thin snow. To the left and right loom trees. They steepen in height the further you walk.

There are brooding hemlocks, tatter-barked yellow birch and reddish cedars. The bushy white pines have a browsed-over look, nipped bare by nibbling deer. Soon the woods seem to darken, closing in overhead. Then you step high over a fallen tree and ascend the knoll. Time travel again.

Concern for Hemlock Knoll is deepened by the knowledge that 1,800-acre Bergen-Brown Swamp in Genesee County is a sanctuary for unusual plants and animals: 30 species of orchids, a rare goldenrod, bog turtles, an endangered pygmy rattlesnake. The swamp is about 10,000 years old, carved out by the last retreating glacier.

| Characteristics of old-growth |

|---|

|

“It’s primeval,” said Chuck Rosenburg, a terrestrial ecologist and one of the researchers who surveyed western New York old-growth. With practiced motion, he trains a pair of binoculars high up the side of one tree, looking for identifying buds 50 feet up.

How do you recognize a tract of old-growth?

There are trees of great size. Trees with twisted trunks, buttress-like roots, and bark cracked into plates—a sign of aging. There’s abundant deadfall, including fallen trees that stand cocked against their living mates. There’s a shaggy canopy above, an abundance of mosses and lichen, and little sign of human disturbance. There’s “pit and mound topography,” gently undulating formations etched into the earth. After a tree topples, it leaves a depression from ripped up roots and a rotting mound beside it.

Bob Leverett measures the girth of a giant red maple in Leolynn Woods. The spiral grain on the trunk is a sign of an ancient tree.  |

|

PHOTO: David Yarrow 2001 |

Hemlock Knoll lacks one traditional sign of old-growth: seedlings, said Battaglia, who was one of the guides in Hemlock Knoll. A forest managed by nature will display trees of every age.

But he speculates that foraging deer, driven by a hard winter, have cropped the tender seedlings back.

At that moment, a jarring modern note breaks into our reverie of a pristine past. Two men in Day-Glo orange hunting gear tramp across the knoll. Each carries a metal deer stand—an ambush platform—retrieved from the woods farther north, now that the season is over.

“We saw 70 deer today,” one said, a little wistfully.

“Just waiting for guys like you,” said Battaglia, making a gun-like motion with his arms. You got the feeling he might start shooting deer out of season, just to protect those seedlings.

But the biggest threat to old-growth forest has never been deer or wind or fire. For 200 year, it has been humans.

“Most of western New York’s forests went up in smoke, literally,” said Battaglia. From 1830 to 1850, farmers cleared the land, burning trees and selling the ash. During that same period, the Hopkins family decided to keep what it had, practically untouched.

| see also: Zoar Valley is gorge-ous Amazed by the tall trees Ecologists find old growth forest Nature’s cathedrals |

|---|

On good days in spring, John Hopkins likes to take in the lay of the land back in the woods. He sees deer, squirrels, great horned owl, fox, and pileated woodpeckers “as big as ducks,” he said.

Hopkins sees a carpet of wildflowers, fern and pencil-high maple seedlings. He can pluck wild leeks out of the ground and eat them. He sees the old beech tree rotting into the earth with a hollow full of bees—”the largest in the woods before it fell down” he said.

Bruce Kershner

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Bruce S. Kershner (April 17, 1950 – February 16, 2007) was an environmentalist, author and forest ecologist.

As a child he resided in Staten Island. Bruce Kershner obtained degrees from Binghamton University and the University of Connecticut. He most recently resided in Amherst with his wife Helene.

He was a renowned old growth forest authority[1], and has discovered almost 300 old growth forests in Eastern North America where previously no one thought they existed.[2] These include the second tallest hardwood forest in Eastern North America, outside of the southern Appalachians, New York State’s oldest forest, and the largest assemblage of old growth (the Niagara River corridor) [3]. Kershner has published a dozen books including the Sierra Club Guide to Ancient Forests of the Northeast[1] and Secret Places: Scenic Treasures of Western New York and Southern Ontario[4].

Bruce Kershner has won numerous awards for his environmental activism. These include ‘Environmentalist of the Year’ in 1987 and 1988 from the Sierra Club (Niagara Group) and the Adirondack Mountain Club, and ‘Environmentalist of the Year in New York State’ in 1996 from Environmental Advocates of New York.[2] Bruce Kershner was serving as the Conservation Chair for the Buffalo Audubon Society.[5]

Bruce Kershner led numerous ecological studies. These have included studies of the Reinstein Woods Nature Preserve, Zoar Valley, Staten Island, Allegany State Park, and the Niagara Gorge. He was working on a research study for legal proceedings associated with the Kortright Hills Community Association in Guelph, Ontario.[6]

Kershner died in February 2007, after battling esophageal cancer for a year and a half.

Effective September 4, 2008, New York State Governor David Patterson signed into law the Bruce S. Kershner Old-growth Forest Preservation and Protection Act,[7] an amendment to existing environmental law that establishes a first in the nation definition of an Old Growth Forest, compels indefinite protection on state land and encourages acquisition by the state where the definition is satisfied on private land.

Bibliography

Buffalo’s Backyard Wilderness: An Ecological Study of the Dr. Victor Reinstein Woods State Nature Preserve (1993) [3]

Secret Places of Western New York (1994) [4]

Secret Places of Staten Island (1998) [5]

Cascades, Cataracts, and Chasms: A Guide to the Waterfalls of Western New York and Nearby Ontario (1998)

Guide to the Ancient Forests of Zoar Valley Canyon (2000)

The Sierra Club Guide to the Ancient Forests of the Northeast (2004) [6]

References

Obituary, Buffalo News, 18 Feb 07.

^ GCL : Ancient Trees Found – A 500-Year-Old Clings To Life

^ Buffalo Museum of Science – Bruce Kershner

^ AMERICAN FORESTS Magazine, Fall 2005

^ Barnes & Noble.com – Books: Secret Places, by Bruce Kershner, Hardcover

^ About Us

^ Innovative Solutions Achieved in Guelph Ontario Municipal Board Resolution

^ 2008 New York State Senate Bill S-4637-C, Assembly Bill A-8145-C

External links

Bio from Alfred University Seminar Series

NYTimes A Rendezvous with 2 Giant Trees

NYTimes A High School’s Teams Challenge The Mighty Oaks

Buffalo Audubon Society

Rogues Gallery of ENTS Members

http://newyork.sierraclub.org/niagara/brucekershner.html

Newsday ‘ ‘Enthusiasm Rarely Seen In This Neck Of The Woods – LI Moment Column

Current